2 Points Here

Point 1) Awareness and Use of the Shared Data Concept

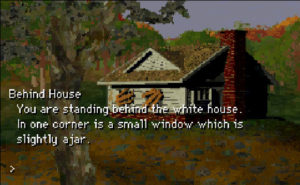

In the early 1980’s, there was the first generation of INFOCOM’s great text adventure game series, Zork I. Being pre-GUI days, this game was completely text and relied on a constantly sustained image of an underworld kingdom fixed in gamers’ imaginations.

To get a sense of the imagery, here’s a bit of the game text from the beginning:

This is an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door.

There is a small mailbox here.

> Go East

The door is locked, and there is evidently no key.

> Go North

You are facing the north side of a white house. There is no door here, and all the windows are barred.

> Go East

You are behind the white house. In one corner of the house there is a small window which is slightly ajar.

> Open Window

With great effort, you open the window far enough to allow entry.

> Enter Window

You are in the kitchen of the white house. A table seems to have been used recently for the preparation of food. A passage leads to the west and a dark staircase can be seen leading upward. To the east is a small window which is open.

On the table is an elongated brown sack, smelling of hot peppers.

A bottle is sitting on the table.

The glass bottle contains:

A quantity of water

> Go West

You are in the living room. There is a door to the east, a wooden door with strange gothic lettering to the west, which appears to be nailed shut, and a large oriental rug in the center of the room.

There is a trophy case here.

A battery-powered brass lantern is on the trophy case.

On hooks above the mantelpiece hangs an elvish sword of great antiquity.

> Take Lantern

Taken

> Take Sword

Taken

> Move Rug

With a great effort, the rug is moved to one side of the room.

With the rug moved, the dusty cover of a closed trap-door appears.

> Open Trap-door

The door reluctantly opens to reveal a rickety staircase descending into darkness.

> Go Down

It is pitch black. You are likely to be eaten by a grue.

Your sword is glowing with a faint blue glow.

> Turn On Lantern

You are in a dark and damp cellar with a narrow passageway leading east, and a crawlway to the south. On the west is the bottom of a steep metal ramp which is unclimbable.

The trap door crashes shut, and you hear someone barring it.

….

For 1982 gamers, this was a fascinating journey through our imaginations. No one had ever experienced a medium that left them feeling so completely consumed by and active in the imaginary world it created. No book or movie or magazine article or comic or TV show was ever as participative. Players remembered their paths through the maze by dropping unneeded articles to recognize their locations, all mapped out in their minds.

It was clear then that the virtual worlds computers can generate would eventually dominate. (And, back then, we had no idea what was yet to come.) Within a couple of years, though, the world had moved on from text adventure games. (It’s too bad a little more time wasn’t spent figuring out the limits of our mental capacities alone for a shared data concept like that experienced in Zork before moving, inevitably, to the visual.) Most fascinating about the shared concept in the text version of Zork was that gamers, whether or not they played together, described visualizing the same surroundings, the same characters, the same features and details. Two or more gamers with no shared visual reference were able to describe in detail their separate but same imaginative visions and descriptions of the troll, the thief, the bloody axe, or the crystal skull.

(Zork’s a great game. It’s now playable online and free. It can be played in an evening: Zork I.

The complete answers are online also.)

Again, within a couple of years of the dawn of text adventures, hi-speed visual games (like Space Invaders) arrived. Zork II and Zork III were released after the dawn of visual games, but the world had looked away and would never look back. II and III never enjoyed the success of I.

Decades later, a Minecraft version of Zork was created:

The Minecraft version is certainly a shared data concept as detailed as the game text above describes, but, unlike the single-player mode of the original text version, the Minecraft world can be shared with others. Two or more gamers can learn together and share resources – together.

End of Point 1

Zork, particularly the text version, demonstrates how users are smart enough to picture in their minds and remember a shared concept, a designed structure, created for them in a virtual world:

- they can remember paths through these complex virtual structures (from memories created back in 1982, I remembered my way through the game in the text captured above);

- they can make use of tools provided for them along the way (Picking up the lantern and sword);

- they can solve problems in the virtual world (When challenged in the dark, I used a tool – the lantern, by turning it on – to solve a problem internal to the virtual world);

- they can, through practice, improve their efficiency in navigating and solving problems in the virtual world (For the benefit of this blog’s readers, I wrote full text commands, such as “Go West,” or “Open Window” to make the explanation clear. When actually playing the game, I used simpler commands, remembered from 1982, such as “w” for west, “e” for east, “open” for open window – efficiencies I’d learned through rote);

- and they can work together in the virtual world with others to solve problems (In the visual, virtual, multi-player world of Minecraft’s Zork, more than one player can review and analyze a problem, discuss solutions, share tools and successes).

Knowing this, how can we as Knowledge and Information managers arrange the information we are responsible for managing in structures suited to user capabilities within virtual worlds?

How can we leverage user “virtual world” capabilities to fix problems with our data?

Virtual worlds don’t have to mean weird headsets with visions in three dimensions. As feebly explained through the example of Zork, gamers (users) have the ability to imagine a structure in their heads – IT’S YOUR JOB TO CREATE THAT STRUCTURE!!!!!!!

Point 2) Brute Force

Zork, the game, can best be described as an adventure which allows the user to move from room to room, collect items, discard items, and use items alone or in combination to solve problems in the game.

From a more elevated level, Zork can be viewed as a collection of automated forms (rooms) to which the user (gamer) is given an unrevealed set of possible text choices (possible command line options) relative to the form (the room) on which the user (gamer) currently finds themselves.

From a Knowledge and Information Management perspective, Zork can be analyzed as a software platform (content management system) on which gamers (users) in Zork (structured process) agreed to be led along administratively-developed routes (workflows), provided with limited unknown answers (text choices) for entering, exiting, performing tasks in any of the game’s rooms (forms).

This is brutally tortuous UX (user experience) packaged in the form of a game to make it fun…and gamers (users) tolerated it.

1 & 2 Together

To a K&I professional, both of these points are powerful knowledge and of tremendous value: Users are extremely tolerant of new, unknown processes, willing to accept limited instruction, can be “mandated-by-process,” and can share a common mental concept in pursuit of a goal.

(It also settles a breakout debate about concerns for the end user and the impact a K&I-centric change may have to their work.)

Government organizations, understanding the mandate to organize their information, can use this knowledge in designing processes to capture data in management systems that allow for infinite data analyses and reuse. Government employees are your workforce. Use them to provide you data as the organization needs it. Provide them the goal, explain the logic of your data structure, and “brute force” your processes, if necessary, to crumble your data so that it best serves your organizational needs.